Becoming a Reflective Practitioner

Exploring our experiences and implementing impactful change.

What is reflection?

Teaching is a continual process of planning, reflecting and adapting, where you learn from your own teaching experience to refine and develop your practice. Dewey (1938) argued that reflective practice promotes a consideration for why things are as they are and how we might direct our actions and behaviour through careful planning. When we underpin this planning with experience and theory, we become much more impactful. To simplify the point, we do not learn from experience, but from reflecting on experience, and it is these lessons we take forward.

When we become reflective about teaching and learning practice, we strengthen our capacity to learn. We build those all-important metacognitive skills and start to examine the gap between what we know and what we need to learn – the basic principle of how we improve. Schön (1983) took reflective practice a little further and defined two processes: reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action.

Put simply, this is the difference between observing thoughts and actions as they occur to adjust in the moment, and the process of retrospectively looking back and learning from experiences to adapt future action.

When do we reflect?

We often assume that reflection is a planned and deliberate action. But in reality, we are reflecting every time we receive feedback, in our conversations with peers and our students, as well as when we provide feedback ourselves.

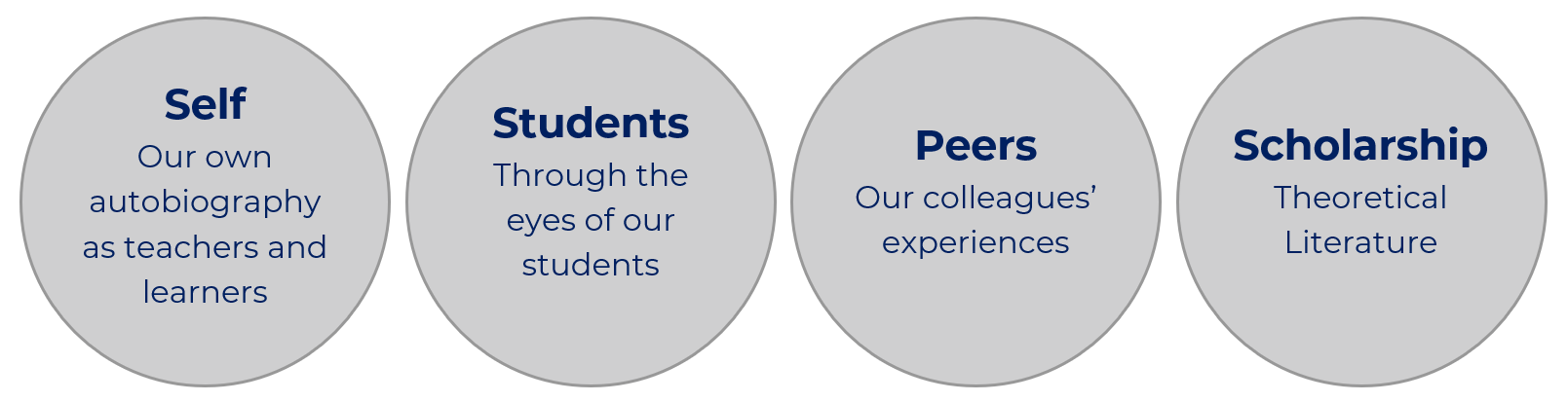

Brookfield (1995) defined four distinct and interconnecting lenses through which teachers discover, examine and critically reflect on their own assumptions and actions.

A good starting point is to look at your own practice through the self-lens, but we should remember to cross reference these thoughts and ideas with the feedback we receive in peer-observations, student evaluations as well as what we learn from engaging with literature and evidence.

Do I have time for this?

It’s easy to ignore reflection because we quite often think it takes a long time. And let’s be honest, if you sit down to with the sole intention to reflect, then yes – it might take a bit of time. But keep in mind all of the opportunities you have to undertake some reflection-in-action.

- Identify what’s working well – why do you think that is? What else could you apply this practice to?

- Students are struggling with a concept – again, why? What could you change?

- There’s some misunderstanding about the task I’ve asked the students to undertake – (you’ve guessed it) why is that? What aspect needs to be corrected or explained further?

It’s probably too late for this to be beneficial.

Reflection is a cyclical process: experience, analysis, implement, repeat. You can incorporate the changes into future deliveries, or into the design of new activities. The changes you identify are very rarely so specific that the learnings cannot be applied elsewhere.

It’s a bit negative though, isn’t it?

No. It’s about growth and adaptation. Identify your strengths and examine how that good practice can be used in other areas of practice. It’s also about experimentation. Not everything will go right. It’s an opportunity to see the practice of others and see if those approaches can be incorporated into your own.

Not everything will stick but take the strengths forward and see how you might adapt the actions that don’t always deliver the intended impact.

How do I reflect?

There’s no restriction on when reflection can happen, and it really doesn’t require any tools other than yourself and your own mind. Having said that, you might want use one of the many models that help you capture reflections. Here’s a couple you may find useful:

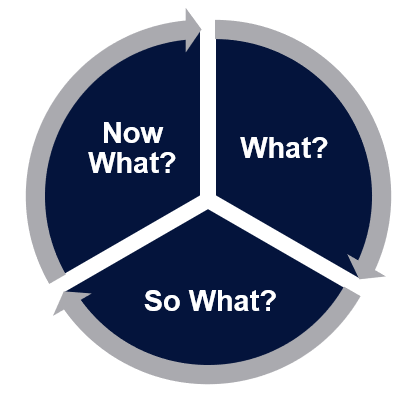

What? So what? Now What?

Driscoll (1994) developed a really simple model for reflection, developed off of the back of work carried out by Borton (1970). Starting with ‘What?’, these three simple questions act as an aid to critically analyse and reflect on an event you want to learn from.

This three-step process enables you to:

- Identify and describe the facts and feelings of the situation,

- Understand the impact of your actions in the situation and the available knowledge you and others had, and

- Create an action plan for future action.

Gibb’s Reflective Cycle

Gibb’s (1988) model steps through six stages for reflection. This logical structure for reflection gives much more explicit prompts to help you engage in descriptive reflection through to critical reflection by asking you to first make sense of the experience, and then identify the improvements to take forward.

Where should I start?

Here’s some suggestions on how you might take more deliberate action to reflect.

Start small

Think about the models above, or one that you identify with most (check out this resource from Edinburgh to explore other models) and start with some simple activities:

- Self-questioning – ask yourself questions that help you examine the impact of your practice

- Experiment – try out new ideas and approaches to create new learning opportunities. You don’t need to redesign an entire lesson; you could start with a small activity and build up

- Have a conversation – discuss your ideas with a colleague. Ask them what works for them and see if there’s anything you could incorporate into your own practice

- Give it structure - explore our own resources on reflection to support your practice.

Create a reflective journal

You might find you prefer to get your thoughts down on paper. This process can be particularly useful if you’re new to reflective practice, new to teaching, or have taken on a new course or topic for the first time.

Think about what elements worked well and what concepts students might have found difficult. You can use these notes down the line to help you develop your materials or activities going forward. Reflection doesn’t have to bring about immediate change.

Reflection as an assessment

You may go one step further and facilitate your own students to become reflective practitioners. Reflective practice is a teaching strategy in its own right and incorporates a number of skills that students may need to develop. You may find it:

- as a learning outcome in a course - asking students to ‘critically reflect’

- as an assessment activity – a summative report asking students to evaluate a case study or scenario and incorporate their own thoughts or experiences

- as an approach to formative assessment – a series of prompts that ask students to reflect on their learning and explore their own progress through a course

Make a habit of it

Reflective practice enables us to develop our practice and become more impactful teachers.

The greatest value of reflection comes when we repeat the reflective process, creating a habit and strengthening our ability to be critically reflective and improve (Jasper, 2013).

Photo by Philippe Toupet on Unsplash

References

Borton, T., 1970. Reach Touch and Teach: Student Concerns and Process Education. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Brookfield, S., 1995. Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco, CA: Wiley and Sons.

Dewey, J., 1938. Experience in Education. New York, NY: MacMillan.

Driscoll, J., 1994. Reflective Practice for Practise. Senior Nurse, Volume 13, pp. 47-50.

Jasper, M., 2013. Beginning Reflective Practice. 2nd ed. Andover, UK: Cengage Learning.

Schön, D., 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think In Action. New York, NY: Basic Books.