![]()

| To become self-directed learners, students must learn to monitor and adjust their approaches to learning. |  |

As a member of faculty, it’s probably fair to assume that you were successful as a student and that over the years you have developed and honed your ability to learn. When faced with a new challenge or subject, you use these skills to analyse what is needed, determine the approach to take, and check your progress.

Because we have these interdisciplinary skills, we often assume that our students will too. We overestimate their study skills and are then surprised when their assignment fails to answer the question, or when they spend time and effort on irrelevant areas.

What the research tells us is that metacognition skills are something that need to be taught and practiced. They are underpinned by the student’s self-belief in their own intelligence and their power to affect outcomes.

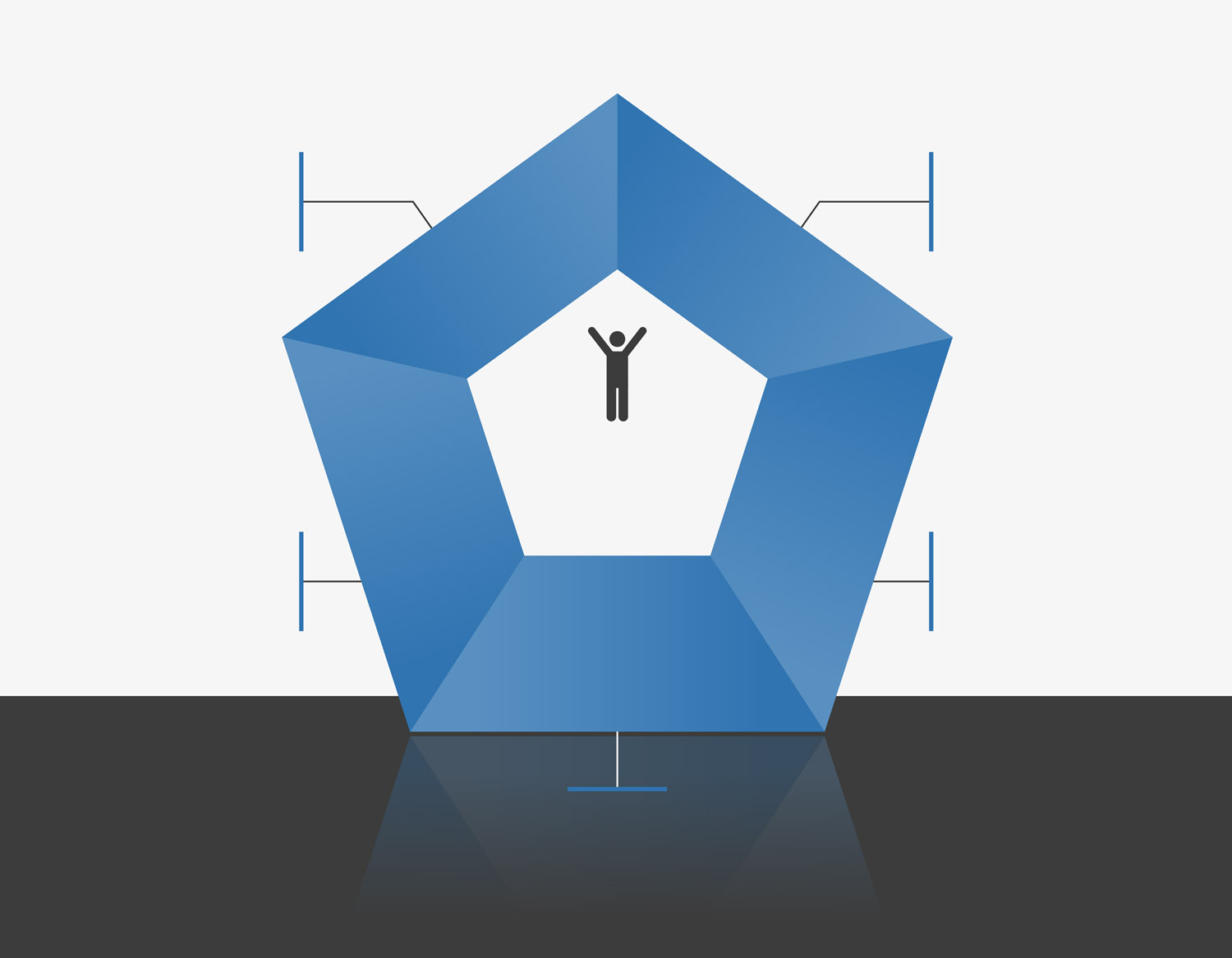

Let’s start by looking at the cycle of metacognitive skills an expert or successful learner will typically follow. We will then look at each of these stages in more detail and some strategies you can adopt to support your students at each stage of the cycle.

- Although it is natural to assume that a basic description of an assignment is sufficient, students may have assumptions about the nature of the task that aren’t the same as yours.

- You can help students by clearly communicating the goals and performance criteria. Remember that learning goals need to be student-orientated, specific and measurable.

- You could either discuss common misinterpretations or share examples of previous work with strengths and weaknesses annotated.

Check students’ understanding of the task

- Give students an opportunity to analyse the requirements of the task themselves and give feedback on the accuracy of their assessment before they begin working on a given task.

- Clearly articulate the criteria that will be used to evaluate students’ work.

- Using a performance rubric that explains what different levels of performance look like helps students assess the size of the task more accurately.

- Encouraging students to self-assess against the rubric helps them develop their metacognitive skills.

Once students understand what’s involved in the task, they next need to evaluate their own skills and knowledge to understand what they need to do to achieve the goal.

So how can we help students in this area?

- Provide students with practice and timely feedback to help them develop a more accurate assessment of their strengths and weaknesses.

- By giving formative feedback early in the process, students have time to adapt and improve their performance.

- Try giving students practice exams or self-assessment opportunities with the answers, so that they can check their own work.

- Remember to highlight that it’s important students do the activity themselves before looking at the answer. Otherwise it can give them an inaccurate view of their own knowledge. Recognising the correct answer when you see it is easier than coming up with the answer yourself!

It stands to reason that if students don’t understand the task or know what their relative strengths and weaknesses are, then they aren’t going to be able to make an effective plan! Even when they do understand the task and their strengths and weaknesses, students still struggle with planning.

- Spending too little time planning in comparison to experts (Chi et al., 1989)

- Not recognising why planning is important and how it can improve their performance

- Creating plans that are inappropriate to the task (Carey et al., 1989)

- For complex assignments, provide students with a set of interim deadlines or a time line for deliverables that reflects the way you would plan the stages.

- Use this as a scaffolding stage to help students learn the elements and sequencing of planning. Do this before having them create their own plan.

- Once students can recognise what a good plan looks like, give them practice and feedback in creating their own plans.

- Make planning their assignment their first deliverable and provide feedback.

- If students perceive that planning is a valued and assessed component of a task, they will be more likely to focus time and effort on planning and, as a result, benefit from their investment.

- To increase practice opportunities, ask students to plan a solution strategy for a set of problems without implementing them.

- This allows students to focus all their energy on the planning skill set and emphasise planning as a valuable activity.

- Submitting plans makes the students’ thought processes explicit for you to review and feedback on.

- You might set a follow - up assignment to implement their plans and reflect on their strengths and deficiencies.

As an expert, it’s natural to monitor the effectiveness of your chosen strategy to make sure it’s working. This isn’t something we can assume students will do automatically. However, the good news is that by explicitly teaching and prompting students to monitor their performance, they can make greater learning gains (Bielaczyc, Pirolli, & Brown, 1995; Chi et al.).

So how can we help students do this?

- Teach students basic heuristics for quickly assessing their own work and identifying errors. For example, making an estimate to compare their detailed answer against.

- There are often disciplinary heuristics that students should also learn to apply. For example, “What assumptions am I making?”

- You can also give more practical guidelines. For example, ‘I would expect this assignment to take you approximately 6 hours.' Students then have a ball-park figure to measure themselves against and to either seek help or change their approach.

- This help students recognise the qualities of good and poor work and teaches them how to monitor their own progress towards learning goals.

- This is a skill you will need to model first. Sharing annotated examples of poor or model answers can be helpful here.

Ask students to reflect on and annotate their own work

- Ask students to complete their own self-reflection on their approach as part of the assignment.

- This helps students become more conscious of their own thought processes and work strategies and can lead them to make more appropriate adjustments.

- Have students analyse their classmates’ work and provide feedback against specific criteria.

- This can help students develop their critical evaluation skills and become more aware of the strengths and weaknesses in their own work.

- Remember to share ground rules on how to provide constructive feedback.

There’s a truism that goes “if you always do what you’ve always done, then you’ll always get what you always got”. However, research shows that people will often continue to use a familiar strategy that works moderately well rather than switch to a new strategy that would work better (Fu & Gray, 2004).

What can we do to help them see the benefit of change?

- What did you learn from doing this project?

- What skills do you need to work on?

- How would you prepare differently or approach the final assignment based on feedback across the semester?

- How have your skills evolved across the last three assignments?

- When students learn to reflect on the effectiveness of their own approach, they can identify problems and adjust next time around.

- An example is an exam wrapper that guides students through a reflection on:

- what types of errors they made

- how they studied

- what they will do differently in preparation for the next exam

- Ask students to review their exam wrappers in the lead up to the next exam to help them adjust their study techniques.

- Have students propose a range of potential strategies and predict their advantages and disadvantages without implementing them.

Self-belief is at the centre of the metacognition cycle. A student’s self-belief about their own intelligence and abilities to learn has a significant impact on their metacognitive development.

Research shows that students’ beliefs in these areas are associated with their learning-related behaviours and outcomes, including course grades and test scores (Schommer, 1994).

A student who considers their ability and intelligence to be set in stone won’t see the value in putting in the time and effort it takes to master a new skill – they are demotivated before they even start. On the other hand, a student who sees their ability as malleable is more likely to engage in positive learning behaviours and study strategies that will increase their performance (Henderson & Dweck, 1990).

- It’s worth spending time with your students talking about their potential for growth and the positive effects of practice, effort and adaptation.

- You might like to use the analogy of the brain as a muscle needing exercise to work at peak performance. Just like an athlete needs to train, we need to exercise our brains with mental discipline and practice.

- Students often believe that “you either know something or you don’t know it.”

- Highlight the different levels of learning and explain that different types of knowledge are needed for different tasks:

- Ability to recall a fact, concept or theory (declarative knowledge)

- Knowing how to apply it (procedural knowledge)

- Knowing when to apply it (contextual knowledge)

- Knowing why it is appropriate in a particular situation (conceptual knowledge).

- Give students realistic expectations about the time it might take them to develop skills. Perhaps share your own frustration at mastering something or stories of how famous figures in your field overcame challenges. This can help students see that learning doesn’t happen without effort.

- This can also help students avoid negative views about their abilities or environment and instead focus on aspects of learning over which they have control: their effort, concentration, study habits, level of engagement, etc.

- Don’t assume that students have the same level of metacognitive skills that you do.

- Expose and model your metacognitive skills.

- Scaffold students in their metacognitive processes with plenty of opportunity to practice with formative feedback.

- Support students in developing a growth mindset.